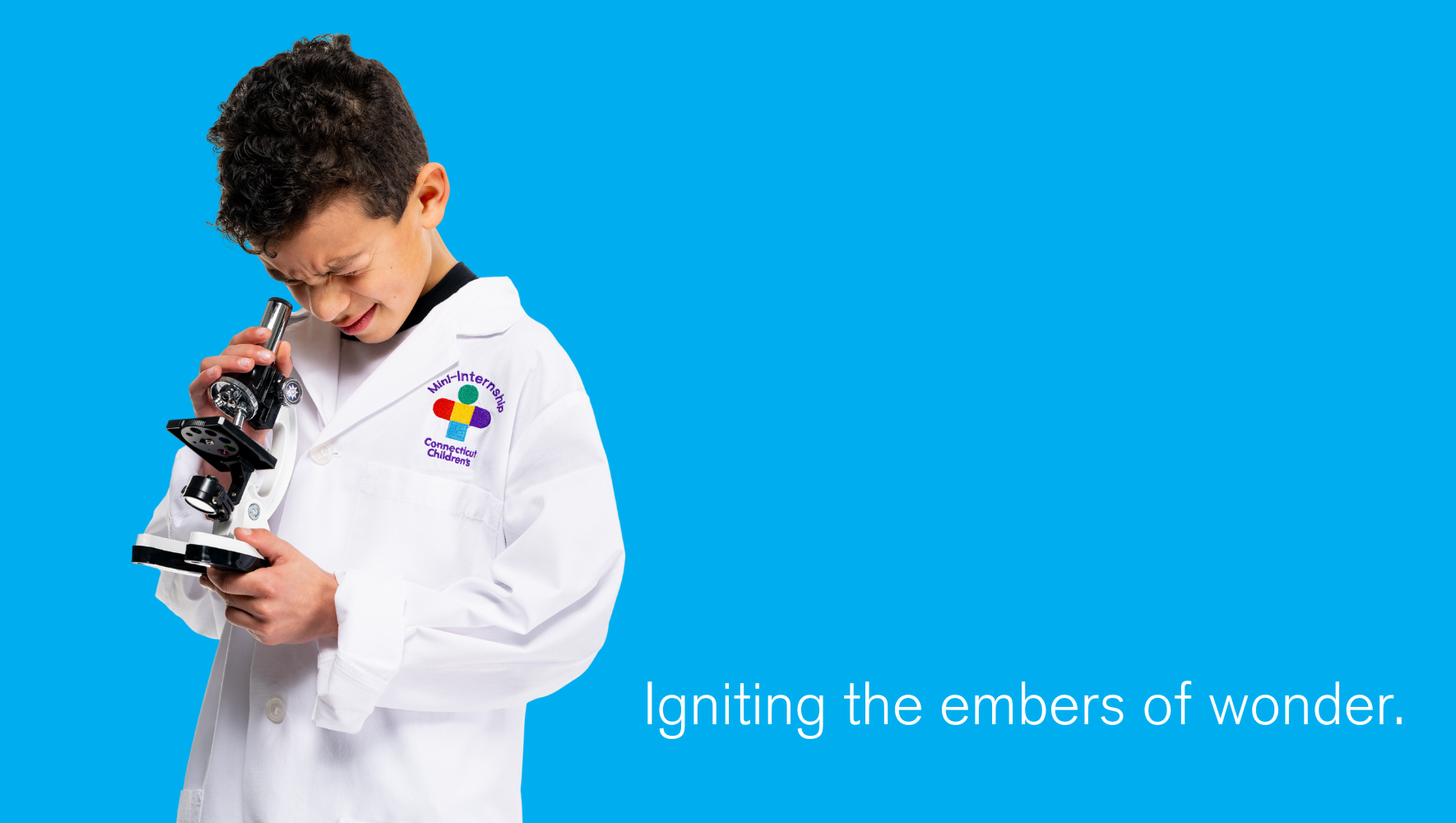

Our vivid imaginations fuel huge breakthroughs and push pediatric healthcare to new heights.

Connecticut Children’s Research Institute (CCRI) is transforming children’s health and well-being. We stand at the intersection of passion and innovation. From groundbreaking research to real-world impact, our mission is to offer new hope for families and kids everywhere. In our labs, we pioneer life-changing treatments using groundbreaking techniques such as gene therapy, stem cell research and 3D bioprinting. Beyond the lab, we incorporate mental health and research aimed at reducing gaps in healthcare to ensure a comprehensive approach to pediatric care. We provide advanced care and improved outcomes for children with complex medical conditions collaborating with premier research partners and experts worldwide. By leveraging our deep expertise across five Scientific Centers, CCRI is not only changing healthcare today, but shaping the future of children's health globally. Join us in making a difference for children everywhere—because every child deserves a healthier tomorrow.