What are the signs and symptoms of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy?

There are about 30 types of LGMD, each divided into smaller subtypes. Even within the same subtype, there can be big differences in how the disease affects each person over their life. Many people eventually lose the ability to walk and need a wheelchair. Others, with less severe conditions, can maintain a lot of their mobility, sometimes with the help of walking devices and special exercises. While there’s no treatment or cure for LGMD, there are experimental gene therapies being explored for a few types, including LGMD2D. But they aren’t available yet.

In the days following Jacob’s diagnosis, Rachel and Josh felt these uncertainties sink in. They took turns crying in a separate room so Jacob and his little brother, Andrew, wouldn’t worry.

Then they began to shift their focus: to what they did know, and what they could do.

Some people aren’t diagnosed with LGMD until later in life. Rachel describes Jacob’s early diagnosis as a blessing in disguise. “We’re grateful we learned about it now,” she says. “We’re ahead of the diagnosis for him.”

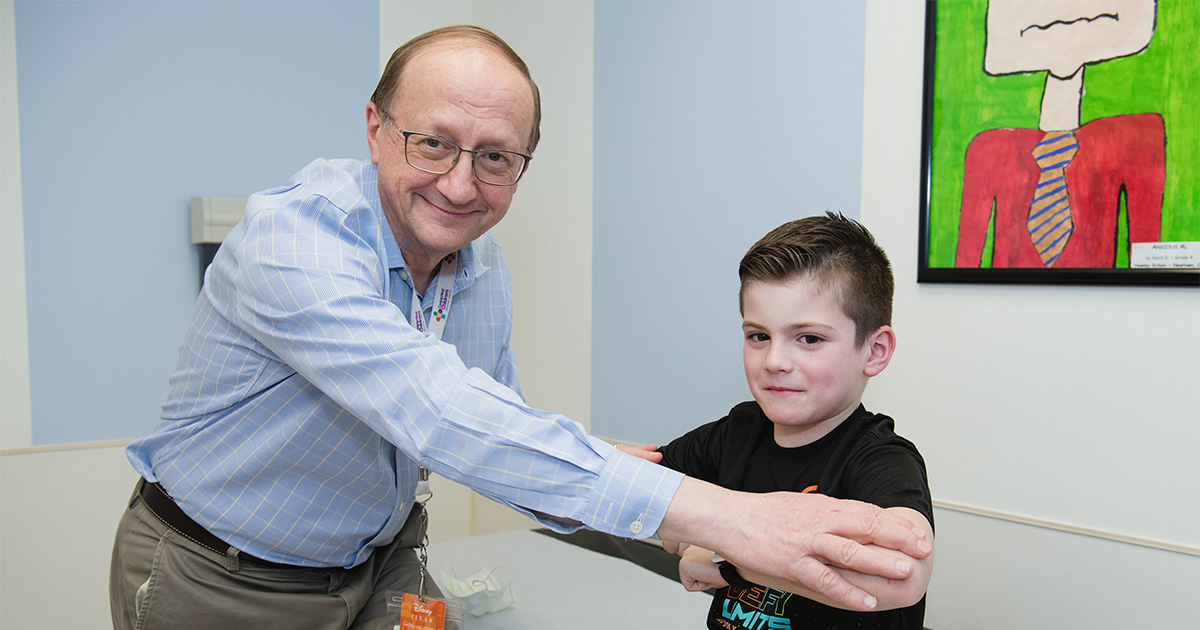

They also feel confident in his care team. In Rachel’s words, “We have Jacob with the best doctors.” She messages directly with Dr. Acsadi on MyChart. This direct line of communication — with the head of Neurology, no less — has always struck Rachel as above and beyond. Right now, Jacob doesn’t need physical or occupational therapy. The most important thing he and his parents need is information about the road ahead.

Natural history study for limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

Finally, they realized that Jacob could help the world understand LGMD, which is the fourth most common type of muscular dystrophy. With Dr. Acsadi’s support, they signed him up for a natural history study based in Ohio. Now, every six months, the family flies out to meet researchers who keep track of how Jacob’s doing, including with physical activities.

Knowing his love of Spiderman and the Avengers, Rachel and Josh first explained these trips to Jacob as Avengers Training Camp. It really is the work of superheroes: By participating, Jacob may speed up the development of LGMD gene therapy — which could help lots of other kids and adults with the disease. Earth’s mightiest heroes, indeed.